Mary Elizabeth (Gilliland) Rakestraw with her great grandson, Sanford “Bud” Wiseheart, circa 1924.

Sanford William “Bud” Wiseheart was born on May 30, 1923 in New Albany, Indiana to Sanford Wesley and Mildred Gertrude (Springer) Wiseheart.1 Bud’s great grandmother, Mary Elizabeth Rakestraw, lived with the family until her death in 1935.2,3 She was the widow of a Civil War soldier and passed down many family stories to Bud and his siblings. In 1941, Bud’s father bought a farm just outside New Albany. They raised crops and chickens. Plucking the chickens was one of Bud’s jobs. He never would eat any poultry after that.

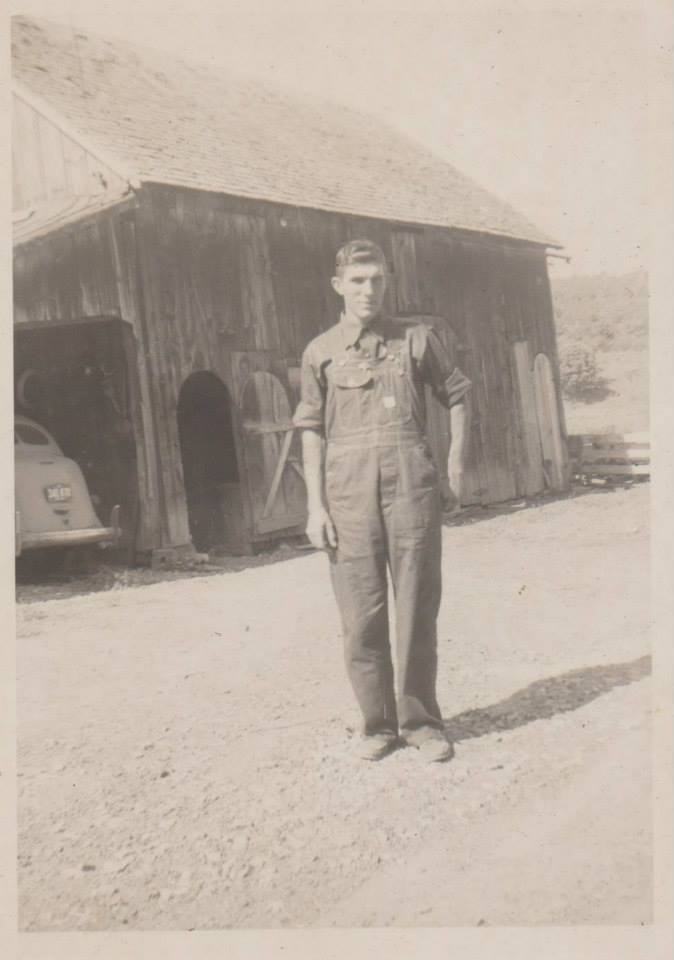

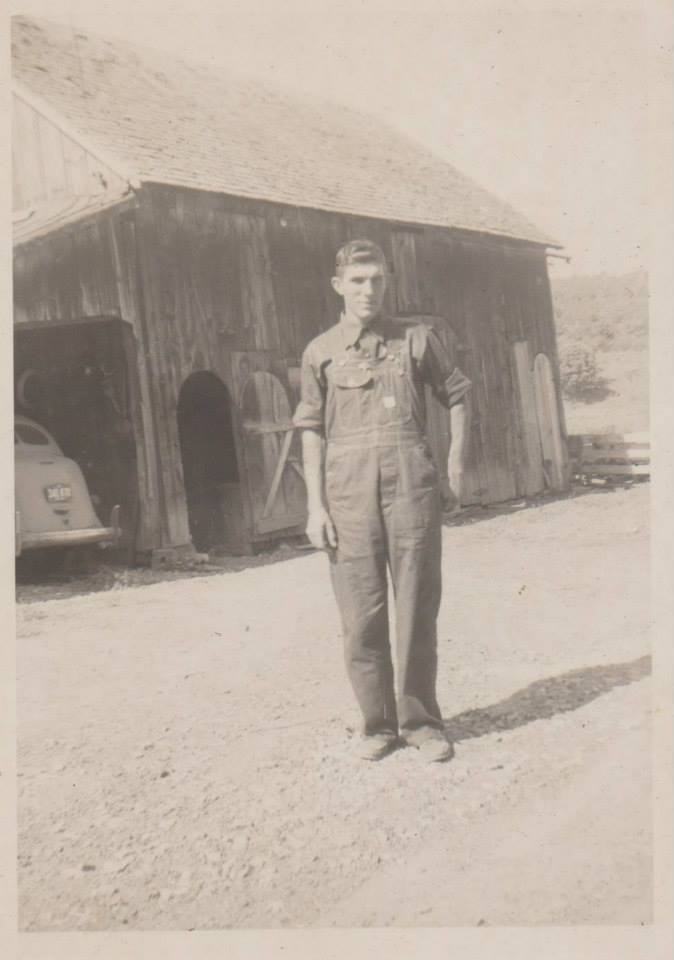

Sanford “Bud” Wiseheart on the farm.

Bud married Dolores Louise Schroeder on August 2, 1958 at Atkins Chapel United Methodist Church in Floyd Knobs, Indiana.4,5,6 (For their engagement story, see Dolores Schroeder). They had four sons.6 Bud was a carpenter. He worked for New Albany-Floyd County Consolidated School Corporation and he also did some freelance work. He was also very active in the church. He was an usher, bell ringer, Sunday school teacher, and maintenance man for Atkins Chapel. He also built the church’s Harvest Homecoming booth and assisted with Vacation Bible School. Bud died at home on October 30, 2014.7

Sanford William “Bud” Wiseheart

My grandpa was a hard working man who didn’t seem to have much to say, but when he did say something, it was more than worth it to pay attention. He was an excellent story teller and knew a lot about a lot of things. Every time he told me a story, it was full of heart. Bud was no stranger to hard times, but he weathered them all. The following is a story, in his own words, that includes two such times:

World War II. I must’ve been nineteen when it started. After a while, they started draftin’ and they had a bunch of us went over to Louisville and we were sent letters that we were to be inducted into the Armed Forces. Thirty three of us went over in that bus from New Albany to Louisville and eleven of us came back rejected.

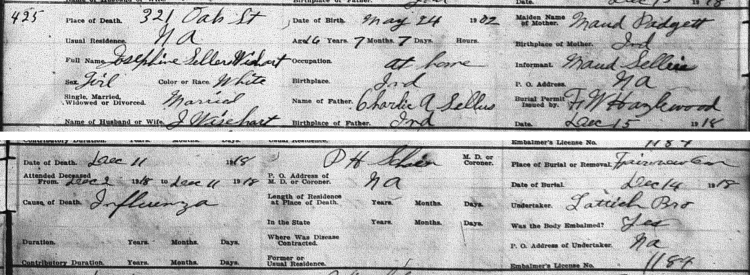

They examined me and I had a bad ear. And the psychologist held me up and asked me all kinds of questions. He asked me what I got out of life. I told him, ‘I like to help other people, my mother and my father.’ And he kept callin’ me ‘Old Man.’ Nineteen years old and he’s callin’ me ‘Old Man.’ He said, ‘Tell me, Old Man, was there ever somebody in your life you loved very deeply?’ And I said, ‘Well, I can’t think of anything right off.’ Of course, what it was, my little sister, Mary Katherine, I used to sometimes change her diapers. I was kind of an interpreter. Sometimes she’d say something to her mother and Ma would ask me what she said. And so, when she was two years old, she walked right past where I was cleanin’ the stables out and into the neighbors’ yard and fell in the fish pond and drowned. That went pretty hard with me. I felt responsible, like I should’ve seen her. I should’ve saved her. I even prayed to God to bring her back and take me in her place…

But gettin’ back to it. I took a heck of a lot of flack. One time I was goin’ to the grocery with Pap and someone remarked, ‘There’s a young man who ought to be in the military.’ Well, now you can’t tell by lookin’ at somebody that they ought to be in the military. I just never did have any desire to shoot and kill anybody, but I never made any effort to avoid the draft.

They sent a notice out, ‘All people that are unfit for military service are expected to get into the defense work to help the cause.’ And if we didn’t go somewhere voluntarily, they were goin’ to draft us into defense work. So I went on up to Charlestown and got in on the construction over there.

My mother got a letter one day from Clara Edwards. ‘My Dear Mrs. Wiseheart, Thank you for your compliments on Albert and Vernon.’ They had both been inducted into the Army, you see. ‘Thank you for your compliments on their nerves. Well, let me tell you something. All you’ll ever see out of the Wiseheart boys is dirty bedsheets, the dirty yellowbacks.’ And then she signed it off. ‘Course Frank was too young and I was 4F, I couldn’t help it. Not that I wanted to go, but they said I was unfit for military service. So anyway, all them years of this hostile attitude.

Sanford “Bud” Wiseheart hanging the flags. July 4, 2009. Photo taken by Sarah Wiseheart of Wiseheart Photo.

Sources

1. Floyd County, Indiana Births, CH-14, p.113, Stuart Barth Wrege Indiana History Room

2. 1930 U.S. Federal Census, Silver Creek, Clark County, Indiana, p.14B, Ancestry

3. 1940 U.S. Federal Census, New Albany, Floyd, Indiana, p.10B, FamilySearch

4. Floyd County, Indiana Marriages, Vol. 55, p.244, Floyd County Clerk’s Office

5. New Albany Tribune, Sun 24 Aug 1958, p.6, c.1, Stuart Barth Wrege Indiana History Room

6. New Albany Ledger & Tribune, Sun 2 Aug 1998, p.B2, c.3, Stuart Barth Wrege Indiana History Room

7. New Albany Tribune, Sat 1 Nov 2014, p.A4, c.3, Stuart Barth Wrege Indiana History Room